I met AJ in April 2014, a mere 6 months ago. His story makes me realize why I do what I do, day in and day out. When I met AJ, he was 9 years old. He had a diagnosis of Autism. His family had relocated from India to Orange County a few months prior to our meeting. His mother later told me that they had made the move specifically because she wanted AJ to receive P.R.O.M.P.T therapy. His mother also revealed how AJ had been through no less than twelve speech therapists, several ABA therapists, and a few occupational therapists. They had also tried Neuro-Feedback therapy; several detox programs, and nutritional supplements, all in the hope that they would help with speech production. After all those setbacks and disappointments, it still amazes me that this family decided to move across the world to try another program. But I guess hope is a crazy thing.

During the initial evaluation, I realized that AJ was truly non-verbal. There were no vocalizations on demand. When asked to say “ah,” he would open his mouth, but there was no sound. He could imitate some lip movements with tactile prompts and cues, but again, without any vocalizations. He did spontaneously babble labial sounds like /baba/ and /mama/, but there was no intentional speech. I realized that at age 9, with little to no progress after years of speech therapy sessions, the odds were stacked against us. When I tried to explain this to his mother, she was quick to respond, “But it can’t hurt to try, right?” I knew then, I had to at least try. P.R.O.M.P.T therapy with tactile cues, in combination with Sara Johnson’s TalkTools® was definitely the way to go.

I saw AJ once a week for 45-minute sessions. His mother would sit through each session, carefully taking notes about the activities and target sounds and words. She would then practice all the activities each day during the week. This video is proof of AJ tremendous progress and his mother’s singular dedication. It was taken after merely 25 sessions of P.R.O.M.P.T. therapy. While there is clearly a long way to go, his incredible achievement so far, makes the future look bright and positive.

Once Sam’s tactile defensiveness was significantly reduced, my next goal was to stabilize his jaw and increase jaw grading (i.e. opening and closing of his mouth to various jaw heights without jaw sliding or jerking). Since Sam tended to “fix” his jaw at jaw height 1 (closed mouth position) during speech, my objective was to move him gradually through Sara R. Johnson’s Bite Block hierarchy. Unless Sam was able to lower his jaw to jaw height 3 or 4, production of vowels such as /Ɔ/ would be challenging. We started with Bite Block #2 and within several weeks were able to move to Bite Block #6, which requires considerable jaw opening. Sam can now hold a lower jaw position without sliding. As a part of a comprehensive oral motor or oral placement program, we also worked on lip rounding, lip seal and tongue retraction. Sara R. Johnson’s Horn and Straw Hierarchy’s were employed for this purpose. In addition, a tongue depressor with added “weights” (pennies taped to both ends) were used to build lip strength and lip closure.

Once Sam’s tactile defensiveness was significantly reduced, my next goal was to stabilize his jaw and increase jaw grading (i.e. opening and closing of his mouth to various jaw heights without jaw sliding or jerking). Since Sam tended to “fix” his jaw at jaw height 1 (closed mouth position) during speech, my objective was to move him gradually through Sara R. Johnson’s Bite Block hierarchy. Unless Sam was able to lower his jaw to jaw height 3 or 4, production of vowels such as /Ɔ/ would be challenging. We started with Bite Block #2 and within several weeks were able to move to Bite Block #6, which requires considerable jaw opening. Sam can now hold a lower jaw position without sliding. As a part of a comprehensive oral motor or oral placement program, we also worked on lip rounding, lip seal and tongue retraction. Sara R. Johnson’s Horn and Straw Hierarchy’s were employed for this purpose. In addition, a tongue depressor with added “weights” (pennies taped to both ends) were used to build lip strength and lip closure.

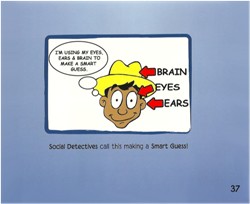

Getting started with the Social Thinking Curriculum by Michelle Garcia Winner is always a challenge. Most of us, Speech-Language Pathologists, fall under two distinct categories: 1) “Read first Therapists” that like to read and study a program until it we can recite it in our sleep before we will begin to implement it on our students, 2) “Try it out first Therapists” that will try to figure out the program while we implement it on our students.

Getting started with the Social Thinking Curriculum by Michelle Garcia Winner is always a challenge. Most of us, Speech-Language Pathologists, fall under two distinct categories: 1) “Read first Therapists” that like to read and study a program until it we can recite it in our sleep before we will begin to implement it on our students, 2) “Try it out first Therapists” that will try to figure out the program while we implement it on our students.

Versus

Versus

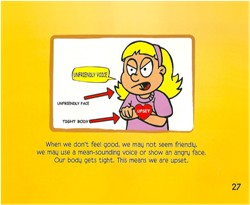

The book also explains “being upset” in explicit physical terms (mean sounding voice, angry face, body gets tight) so children can identify their own states when they get upset.

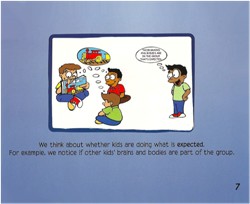

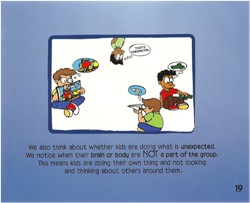

The book also explains “being upset” in explicit physical terms (mean sounding voice, angry face, body gets tight) so children can identify their own states when they get upset. Another challenge a lot of my little ones have is identifying and differentiating between peers who are nice and friendly and others who say or do mean things. The book has tables (page 44 and 45) to help the child identify and list characteristics of a “nice person” and a person who is “not nice to talk to.” In addition, the book also has a glossary with definitions of the Social Thinking vocabulary for quick reference. The book also includes three lesson plans at the end of the book for “Expected Vs Unexpected Behaviors,” “Social Spy,” and “Social Detective.”

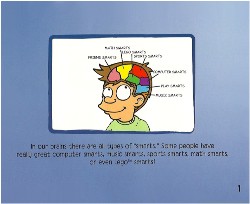

Another challenge a lot of my little ones have is identifying and differentiating between peers who are nice and friendly and others who say or do mean things. The book has tables (page 44 and 45) to help the child identify and list characteristics of a “nice person” and a person who is “not nice to talk to.” In addition, the book also has a glossary with definitions of the Social Thinking vocabulary for quick reference. The book also includes three lesson plans at the end of the book for “Expected Vs Unexpected Behaviors,” “Social Spy,” and “Social Detective.” A majority of my caseload includes preschool and early elementary aged students. Many of them are diagnosed with Autism or demonstrate social skill deficits. If you’re like me and work with the younger students, you know how hard it is to find social skill programs that are structured, but still age appropriate. For the last year or so, the Social Thinking Curriculum has been the go-to program for many therapists to build social skills. However, finding materials that are appropriate for this age group has always been a challenge. In many settings including the public schools the Social Thinking curriculum isn’t incorporated until upper elementary or middle school years. Does that mean that the Social Thinking Curriculum isn’t appropriate for the preschool age group? In my opinion the preschool and early elementary age group is ideal to begin teaching the Social Thinking Curriculum. Introducing the Social Thinking vocabulary and concepts early on makes them a part of their everyday lives and routine. It does present unique challenges though: 1) teaching the vocabulary in ways that makes sense to younger students and 2) preparing lessons that are age appropriate, engaging and flexible.

A majority of my caseload includes preschool and early elementary aged students. Many of them are diagnosed with Autism or demonstrate social skill deficits. If you’re like me and work with the younger students, you know how hard it is to find social skill programs that are structured, but still age appropriate. For the last year or so, the Social Thinking Curriculum has been the go-to program for many therapists to build social skills. However, finding materials that are appropriate for this age group has always been a challenge. In many settings including the public schools the Social Thinking curriculum isn’t incorporated until upper elementary or middle school years. Does that mean that the Social Thinking Curriculum isn’t appropriate for the preschool age group? In my opinion the preschool and early elementary age group is ideal to begin teaching the Social Thinking Curriculum. Introducing the Social Thinking vocabulary and concepts early on makes them a part of their everyday lives and routine. It does present unique challenges though: 1) teaching the vocabulary in ways that makes sense to younger students and 2) preparing lessons that are age appropriate, engaging and flexible. Appendix A describes the story structure. The first edition contains the social dilemmas, while the second provides solutions so the ending is a preferred ending.

Appendix A describes the story structure. The first edition contains the social dilemmas, while the second provides solutions so the ending is a preferred ending. Appendix C provides a visual script for the lesson.

Appendix C provides a visual script for the lesson. Appendix G provides a visual link between people’s thoughts and their feelings. This could be a very powerful and versatile tool. It could be used for far more activities than just the lessons in this program.

Appendix G provides a visual link between people’s thoughts and their feelings. This could be a very powerful and versatile tool. It could be used for far more activities than just the lessons in this program.